Pacing Problems in RTS Campaigns

Peaks and valleys, peaks and valleys

I started writing about real-time strategy games in 2016, beginning with a short little article on the professionalization of competitive real-time strategy. Even all the way back then, I felt that there was a gap in my knowledge on the campaign side of things. I had never engaged much with campaign content during my time with real-time strategy. And while that never prevented me from writing about competitive play, I always had this nagging sense of a hole in my resume, a limitation in my ability to write more broadly about the genre.

(A funny anecdote: when I played in the World Cyber Games US Championship in Orlando, FL in 2007, I happened to sit down with competitors from different RTS games during the finals run of Project Gotham Racing. I realized during our conversation that none of us had any familiarity with the actual story of our games - we were all too busy grinding 1v1!)

A close friend had always bugged me about playing through the StarCraft II campaigns, and I eventually relented and gave them a go in early 2018. I was surprised to discover that they were actually really great. And so I spent the ensuing years playing a variety of different RTS campaigns - Warcraft III, They Are Billions, Northgard, Bannermen, Grey Goo, and so on. One day it dawned on me that I had become just as interested in the single-player side of the genre as I was in ranked 1v1; I even decided not to review Age of Empires IV until fully completing all four of its (fairly length) campaigns.

In short, it’s been a lot of fun becoming a “campaign guy”. And I credit my stronger connection to the “average Joe RTS player” to all the time I’ve spent with single-player content. But sadly, the more I play RTS campaigns, the more I realize that many of them are simply not that great. And I actually feel that they frequently make the same mistakes - consistent patterns of bad behavior, repeated in game after game, rather than isolated incidents of shoddy work.

I had an idea awhile back to write some commentary on the most egregious anti-patterns I’ve observed over the years. The goal is to identify patterns that noticeably lower the quality of the gameplay, and when repeated throughout a campaign, become an anchor on the player’s ability to enjoy it:

Build-a-base-itis

Pacing problems

Scripting disasters

Repetition and padding

Lack of creativity

Abusing the Fog of War

I feel like I speak about build-a-base-itis quite a bit, so I figured I would give that a rest for today, and talk about something else: pacing.

Pacing Problems

When I think about pacing in computer games, the first thing that comes to mind is action-adventure type games - your average open-world RPG, say, or a Soulsborne, stuff like that. I feel that I’m especially sensitive to poor pacing in those types of games, perhaps because I subconsciously identify with the player character. I get this nails-on-a-chalkboard sense of dread dragging my guy through a game’s progression mechanics when I feel like I’m waiting for “the good stuff”. I recall Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel in this context - a mechanically solid game, with good writing, decent graphics, I mean everything you’re looking for, really. But they paced it really poorly, and that dragged my whole experience down with it.

I don’t think people usually think about pacing when it comes to real-time strategy campaigns. I mean, I could be completely wrong on that - I’m basing this on anecdotal reads of Internet forums over the years. But it makes sense, right? Pacing feels like less of a concern in games where the single-player consists of stand-alone missions with a clear beginning and end, rather than a single continuous experience of peaks and valleys. And this is especially true in real-time strategy, where the pacing is almost built-in: a setup cutscene, a base-building phase, a fighting phase, a wrap-up phase, and a closing cutscene.

I think it’s a mistake, though, to overlook pacing. I think it’s worth asking what it’s like to play a campaign mission, moment-to-moment. Maybe a more general way of saying this is that it’s worth asking what a game feels like to play, but I think it goes beyond that. I think level designers should really ask themselves, on a practical, nuts-and-bolts level: even if we assume the gameplay itself is paced well, does that mean each individual mission is paced appropriately, too?

Let me see if I can explain with an example. Take The Hunter of Shadows, the fifth mission from the Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos Orc campaign. The gist here is that a really powerful enemy has come to attack your Orc encampment, and they can’t be defeated unless you unlock a particular magic which is accessed by clearing through a long path on the northern side. While you macro up and clear this up, your base is subject to periodic attacks by the Night Elves on the western side of the map:

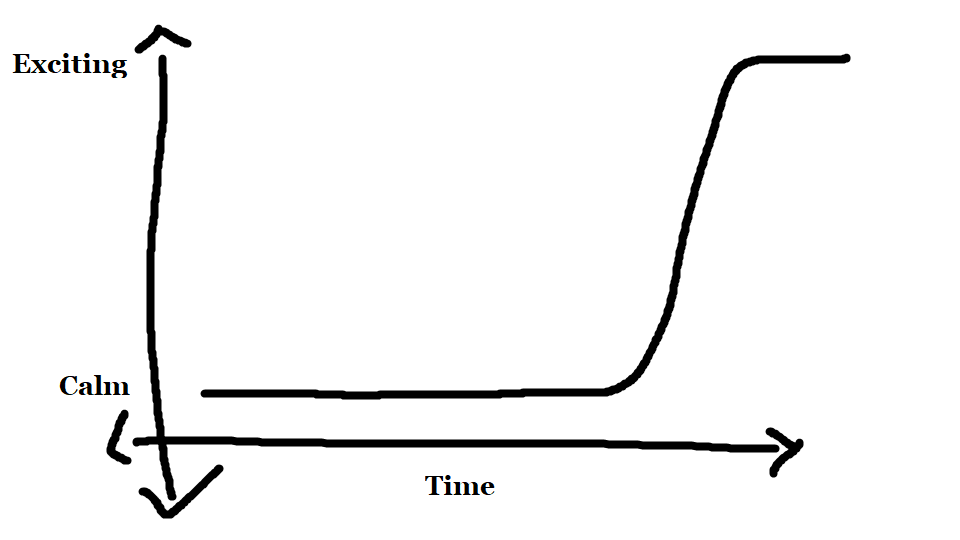

It’s straight-forward enough. But the problem I have with this mission is its pacing. The Night Elf attacks are a serious enough threat that they require a significant resource commitment to defend, either through large amounts of static defense, or by rallying your main army back to your base. Neither of these produces a good end-to-end game feel. For starters, here is how I would describe the best-case scenario excitement / calm curves for each scenario, starting with the static defense case, which requires a long, fairly tedious build-up, followed by clearing the map:

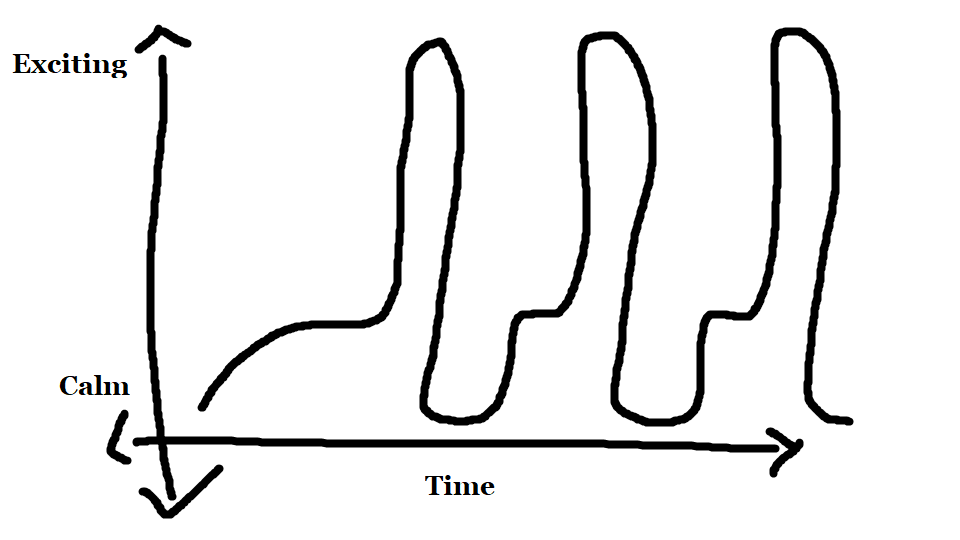

In the main army case, the build-up is smoother, with the player moving out to clear some of the map, retreating to defend and re-build, then going out again, and so on until the mission is complete:

But, in either case, you can’t be sure whether you have enough at home to defend the next attack without taking significant losses, meaning the smoothest approach is to be extra disciplined and patient: clear a little, wait for a big attack, defend it efficiently, clear a little more, retreat, and so forth. The actual pacing of the mission ends up looking like this:

And if you’re impatient like me, you end up over-committing to clearing the map and under-committing to defend, resulting in something more like this:

The problem is two-fold, from my view: one is that there isn’t a good flow from valleys to peaks, because you constantly find yourself running back to defend a big attack, tediously rebuilding what you lost, and then hurriedly moving out to clear some more of the map before you have to race back. Two is that the player has limited agency over this flow, because their army isn’t very mobile and they don’t know when the next attack is coming or how powerful it’ll be; they end up defaulting to an excessively conservative style of play.

(I think IGN is actually underselling it when they describe this as “one of the longest, most grueling missions in the game”.)

I think The Hunter of Shadows ends up this way due to lack of intentionality in its arrangement of peaks and valleys of action - ensuring that they flow from one to the other in an enjoyable way. I think, in particular, the tuning of the mission to require periodic rebuilds ends up throwing things off balance, because the player never really feels in control of their own destiny. You feel like you’re forced into the peaks just to make progress, and forced into valleys just so that you don’t get wiped out, and the whole thing ends up feeling frantic.

I much prefer the way Heart of the Swarm’s Domination structures a similar premise. You’re again periodically fighting an unkillable enemy, in this case Zagara, while clearing the map to make her vulnerable. But this mission does a number of things differently:

The map clearing is action-packed but relatively easy; you’re kinda steamrolling during that phase, so you don’t feel stressed about the impending attack.

The Zagara fights are challenging, but they’re pre-announced and intentional peaks in the pacing.

The map is designed with your army’s mobility in mind; it’s easy to intercept Zagara’s attack regardless of wherever you happen to be.

In combination, these factors force the “disciplined” approach to The Hunter of Shadows, but with a smoother and more intentional curve:

The net effect is that the same general concept ends up being executed in a much more fun and enjoyable way. I fondly remember Domination as an action-packed brawl, repeatedly clearing out the map and heading back home to take Zagara down; I feel like it captures the intent of the premise very well, in which the player is racing to grow more powerful than a seemingly invulnerable enemy. By contrast, I remember The Hunter of Shadows as a mission where I kinda limped my way across the finish line as a dragon repeatedly steamrolled me - I’m guessing that was not the intent, given the mission’s introduction of the powerful Chaos Orcs.

Be Intentional

I hope that was an illustrative example. I get that these two missions are not exactly directly comparable, and that they are also from two entirely different games; but the broader point I’m trying to make is that intentional arrangement of peaks and valleys is a thing that RTS level designers should do, and when it’s not done well, it can mess up the execution of an otherwise interesting concept.

If that all makes sense and you’re still with me, then I’d like to start talking about a bunch of other pacing pitfalls that can make or break a mission. I suppose I should start with the most obvious, which is when a mission leans too heavily on its base-building component: build a bunch of stuff, create a deathball, a-move, and win. This can work when used sparingly, but becomes unsatisfying when it is overused as a design trope:

One of the big things I think level designers miss here is that players factor in their experiences from previous levels into their approach to new levels. So, while your first one or two build-up-and-win levels might have an enjoyable pacing, by the third or fourth level, players might be getting a little antsy, and they may push themselves to close things out before they’re actually ready. When this doesn’t work out for them, they restart and play too cautiously, which makes the experience tedious, even though that’s not the intention.

I mean, I get it - I’m an impatient person, so maybe I’m biased toward seeing this as a bigger problem than it is. The high-level point I want to make is that while it may seem like missions in a campaign are standalone, that’s not necessarily how players experience them. If they’ve been trained to approach the game in a particular way by preceding missions, they bring that training along with them, even if that’s not what the level designer wants.

I think a good solution to this is again the concept of intentionality; specifically, anchoring a mission around an intentionally designed time table instead of letting players decide on their own how long a mission should take. That way, the impact of what players carry from mission to mission is lessened, and each mission stands up better on its own. And while I think it’s good to obscure this intentionality from the player so that they don’t feel like a puppet, I don’t think it’s necessarily always essential, either.

Take Age of Empires IV’s The Battle of Mohi: it straight-up sets a timer on players’ macro phase. But it cleverly obscures this by tying the end of the macro phase to a fun reward (a big friendly army coming across the map), so players don’t feel like they’re racing against the clock: instead, they’re just building up in anticipation of an event they’re looking forward to. I found this design to be a significant improvement over the earlier The Great Wall, which drags due to its uncapped macro phase.

(For the record, I don’t consider The Battle of Mohi to be a particularly good mission, in large part due to its padded ending phase. But I thought the time-constricted macro was clever and worth calling out as a highlight.)

Another really cool approach is Wings of Liberty’s The Devil’s Playground, which has separate and intentionally designed macro and micro phases. Players structure their gameplay around the rises and falls in lava, which paces out the mission really well; players also operate with an appropriate amount of urgency due to the level designers limiting how many minerals there are on the map.

Then there’s the various missions in which players need to defend a fixed location against periodic attack waves, like Warcraft III’s March of the Scourge; there are a ton of variations on this, including Wings of Liberty’s The Great Train Robbery. I think these consistently end up paced out pretty well because the peaks and valleys are all intentionally scripted.

Perhaps my favorite approach - though one that’s hard to do, for sure - is when a mission is structured to have some ongoing component that players hook into. This has the same basic structure as the “attack waves” concept - like asking players to periodically attack trade caravans that cross the map - but it masks it better, and makes a mission feel more dynamic and vibrant. The Battle of Zhongdu, from Age of Empires IV, is a reasonable example of this type of pacing (although executed horribly due to other concerns, especially around map size and scope); Bannermen’s Sought-After Wagons is also pretty decent.

Figuring It All Out

The last thing I want to touch on is just the nature of the genre itself: real-time strategy calls for players to both figure out what they’re supposed to do and play the game, at the same time. And this is challenging from a pacing perspective because levels need to give players sufficient space to figure out what to do without slowing the gameplay down to a crawl, or forcing players to trial and error their way through a campaign by restarting a mission a bunch of times.

StarCraft II handles this well by structuring the first half of each campaign as an introduction to specific units and mechanics. This simplifies the strategic side by encouraging players in one direction - hey, this is the Viking mission, you should build Vikings - for at least the first dozen or so missions. An underrated benefit of this is that since the strategy side is simplified, it’s easy for the designers to insert a lot of intentional pacing to the missions, which means players don’t self-teach themselves bad habits like macroing too much or moving out too early. The game trains them, implicitly, as to how they should approach the game.

Contrast this with Age of Empires IV, which has numerous missions which call for the player to simply macro up and move out. There is usually some trick that makes each mission both unique and easier - using a specific siege unit, say, or building a lot of cavalry - but it’s hard to figure this out at the same time as macro’ing. At least in my case, that motivated me to just build up a big deathball everytime.

(As it turns out, Rus Knights are pretty good.)

The more campaigns I play, the more I think level designers need to be careful in how much open-ended strategy they insert into individual missions. I find that the best executed strategy content in this space is structured, often directing the player in one or two clear directions. The best-feeling missions offer a set of reasonable choices and let players decide among them, instead of saying “here’s a base and a problem, figure it out”. They then take more minor battle tactics and micromanagement and so forth and elevate their role, to give the player a stronger sense of agency and control.

Final Thoughts

I think the highest level point I wanted to make from this - and apologies if my thoughts come across as a bit scattered - is that level designers should have an idea in their head of what it’s like to enjoy playing a mission, and then they should leverage direct and indirect mechanisms to get players to play the mission in that way. I think a lot of campaign scenarios fail, ironically, because they try to offer players too much flexibility and too large of a creative sandbox. It’s hard to design solid pacing if you need to design for the player doing, well, literally anything. I actually think being disciplined in constraining this and focusing on one or two important ideas produces a meaningfully better experience for the end user.

Hope you enjoyed this one folks! I’ll catch you next time.

Until next time,

brownbear

If you’d like, you can follow me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, and check out my YouTube and Twitch channels.

Great and long article ! Indeed War3 pacing can be bad on some mission, but it's was released so long agoooo, i prefer the part when you talk about SC mission since it's more recent, i wing WoL got one of the best campaign in the RTS'style you have everything in it, plus, a good story to follow